Part 1: This is a new subtitle

BY ROBERT LOERZEL

In 1914, Carl Sandburg called Chicago “Hog Butcher for the World.” Edgar Lee Masters, a Chicago lawyer born in Kansas, was giving voice to the common folk buried in a cemetery in the fictional town of Spoon River. Other writers scattered around the prairies, like Kansan William Allen White and Hoosier James Whitcomb Riley, were drawing attention with the craft of their words. The Midwest was teeming with creativity.

But when John M. Stahl looked at the condition of the local literary scene, he decided that the region’s authors needed an organization. Stahl, who’d published magazines for farmers, noticed that New York, Boston, and other Eastern cities had more literary organizations and events than Chicago did. “It was rare that a foreign author of note came farther west than Niagara Falls,” he observed. [1]

Stahl (1860-1944), who was born in Mendon, Illinois, [2] never achieved fame as an author, but he came up with the idea for the Society of Midland Authors, which is still going strong a century later. “Mr. Stahl wrote six books, now deservedly forgotten, but he had a feeling for the better things of literary life and it was his idea to form a society of really top-notch Illinois writers,” Chicago Tribune book critic Fanny Butcher (a later SMA member) once remarked. [3]

With help from fellow writers Mason Warner and Douglas Malloch, Stahl invited Illinois authors to a meeting. As Stahl later recalled, they believed the group should include “those authors who stood for decency and, of course, only those whose work had been recognized as highly meritorious.” And they wanted to “keep out those who had created ill feeling toward and contempt of Chicago.” [4] Stahl loathed modern literature, like the avant-garde stuff that Chicagoan Margaret Anderson had begun publishing in her influential journal, The Little Review, in 1914. Anderson and her ilk “gained a measure of notoriety in Chicago and brought discredit on not only that city, but on a wider territory,” Stahl wrote later in his memoirs. “They wrote bizarre prose or poetry and larded it well with filth. They thought that which was not vulgar was puerile.” [5]

‘I believe in the West and its authors’

Stahl wanted to see authors from the Midwest—or the Midland, as he preferred to call it—writing more wholesome literature about the places where they lived. “The Midland authors have not made their own country loved because they have not taken the characters or scenery that lay right at hand,” he told the Christian Science Monitor in 1915. “You can pick up any hundred books produced by the Midland authors, and you will find less than five per cent have stayed at home in their stories. I believe in the West and its authors. They have not appreciated themselves. They will, however, gather strength by association.” [6] The way Stahl saw things, the region’s “decent authors” needed to make more noise to get their books noticed. And he believed an organization would help them to make that noise. That’s the idea that gave birth to the Society of Midland Authors—but thankfully, the group did not follow Stahl’s narrow-minded views of what qualified as “decent literature.” It turned out to be a group open to writers of styles across the literary spectrum.

“None but a bold man would have sought to weld such individualistic—dare I say egotistic?—creatures as authors into a society of any sort,” said one of the authors Stahl roped into his fledgling club, Hobart Chatfield Chatfield-Taylor. “…Invitations were sent to Midwestern authors to come to Chicago for the purpose of breaking bread and uniting in the spirit of friendship and common bond. Some of them might have even met Stahl’s rigid criteria for ‘literary decency’ and unabashed civic boosterism.” [7]

This wasn’t the first crusade in Stahl’s life. Earlier, he’d been a leading voice for better roads and rural mail delivery. “Having the vision of getting the authors together was just one of his many constructive ideas which he put into action with Napoleonic strategy and energy,” wrote playwright Alice Gerstenberg, one of the writers Stahl recruited. “A small man, he compensated as a dynamo as often happens. Always courteous with a bit of French gallantry, he gave me reason to remember him most sympathetically and kindly. Some people were aggravated by his overall eagerness to make a success of the SMA, but then, most people never even try to exercise the second commandment, they are so busy looking at the outside of a fellow without taking an accompanying glance at the inner soul. I admire people who have the initiative to put something worth while into the world as against those who remain lumps of criticism in the path.” [8]

Despite Stahl’s qualms about modern literature, he invited one of the movement’s leaders, Harriet Monroe (1860-1936), the publisher of Poetry magazine. In his memoirs, Stahl wrote that “some of the things she has helped to build would better never have been aided.” He admired and respected Monroe, but he also knew that she had contempt for his ideas about poetry. She considered him “hopeless” because he liked Victorian literature and the poetry of Whittier and Longfellow. [9]

Monroe, a Chicago native, had written poetic odes for two of the city’s most momentous ceremonial events of the Gilded Age. When the grandiose Auditorium Building, designed by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler, opened on December 9, 1889—becoming the largest building in the world at that time—Monroe’s “Auditorium Festival Ode” was performed with musical accompaniment. Her verses described the Auditorium as a place where liberty and democracy would triumph against the evils of anarchism: “The loving arts shall ease thy breast of pain.” [10]

Then she wrote a poem marking the four-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America, which an actress recited on October 21, 1892, when the city was dedicating buildings for the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition. The crowd inside the enormous Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building in Jackson Park was estimated at 140,000, but it’s likely that only a few thousand were able to hear Monroe’s words: “Columbia! on thy brow are dewy flowers.” [11] She was paid $1,000 for the poem, but she got another $5,000 by suing the New York World after it published it without her consent. [12]

‘No poet can pay his shoe bills’

But Monroe quickly discovered how little money poets earn. Few people bought copies of her “Columbian Ode.” “So all that winter I used the ode for fuel in the little stove which heated my bedroom-study,” she recalled. [13] Recounting that story, The Encyclopedia of Chicago observed: “In a city dominated by economic interests and lacking in literary traditions, even the most genteel efforts to boost literature’s cultural importance had limited influence.” [14]

But Monroe quickly discovered how little money poets earn. Few people bought copies of her “Columbian Ode.” “So all that winter I used the ode for fuel in the little stove which heated my bedroom-study,” she recalled. [13] Recounting that story, The Encyclopedia of Chicago observed: “In a city dominated by economic interests and lacking in literary traditions, even the most genteel efforts to boost literature’s cultural importance had limited influence.” [14]

Monroe could not find a book publisher to print a volume of her poems, and she fumed, “No poet can pay his shoe bills.” [15] She also remarked: “The minor painter or sculptor was honored with large annual awards in our greatest cities, while the minor poet was a joke of the paragraphers, subject to the popular prejudice that his art thrived best on starvation in a garret.” [16]

Monroe wrote art reviews for the Chicago Tribune, including one that declared: “Modern art is a huge democracy, an arena of the many, not the few.” [17] But her dream was to start a poetry magazine. On June 23, 1911, Monroe told Chatfield-Taylor about the publication she wanted to create. He suggested that she persuade a hundred men in Chicago to pay her fifty dollars a year up-front for a five-year subscription, giving her $5,000 to try out her “hazardous experiment,” as she later called it. The key, he said, was that she had to go to their offices and make the plea in person. And, she later said, “It proved easier than I had expected.” [18]

She published the first issue of Poetry: A Magazine of Verse on September 23, 1912. “We believe that there is a public for poetry, but that it is scattered and unorganized,” Monroe wrote in an advertisement for her magazine. “Poetry has no organ to speak for it, and its public does not know where to find it.” [19] After Rabindranath Tagore, whose poetry had been published in the magazine, won the Nobel Prize in literature in 1913, Monroe said, “I drew a long breath of renewed power and felt that my little magazine was fulfilling some of our seemingly extravagant hopes.” [20] In Poetry’sMarch 1914 issue, she published Sandburg’s poem “Chicago,” which came to define the city in the public’s mind.

“Harriet Monroe found in Sandburg’s liberated, dissonant poetry—as well as that of Masters, Vachel Lindsay and many others—exactly the sort of unconventional work she wanted for new journal,” Chicago Tribune Book World editor John Blades would write in 1983. But others, including The Dial, a patrician literary journal published in Chicago, “disapproved of the spoken, proletarian cadence of Sandburg’s poems, refusing even to acknowledge that they were poetry.” The Dial called it the “hog-butcher” school of verse. [21]

‘The audience was quite carried away with his gusto’

On March 1, 1914, Poetry hosted a banquet in honor of the legendary Irish poet William Butler Yeats, who was visiting Chicago. The guests included many of the authors who would soon join the SMA. When Yeats spoke, he praised a poem he’d read by Lindsay, “General Booth Enters Into Heaven.” “This poem is stripped bare of ornament; it has an earnest simplicity, a strange beauty,” Yeats said. And then it was Lindsay’s turn to perform a brand-new poem called “The Congo” for the assembled literati. “Only a few of us had ever heard Lindsay recite his poems: the audience was quite carried away with his gusto,” Monroe recalled.

And yet, like so many poets, Lindsay wasn’t making much money. Earlier, when he accepted Monroe’s invitation to attend the Yeats banquet, he’d written to her from his home in Springfield, Illinois: “I am sorry you will have to pay my car-fare, but I am dead broke. Can’t you advance me what the poems are worth that you have on hand?—I don’t want to be an extra expense. My plan of life is very simple, you see—to live at home—on nothing. I only notice my empty purse when people ask me to go places.” [22]

“Sandburg, Monroe and other Chicago novelists, poets and editors were at the vanguard of a revolt—a revolt both from rural values and from the genteel literary tradition that had prevailed in Chicago since the 1871 fire,” John Blades noted in his essay about the era. At the time, they were considered vulgarians by the contemporary literary establishment; its exemplars included such Jamesean disciples as Hamlin Garland, Henry Blake Fuller and Hobart Chatfield-Taylor…” [23]

‘This is where I belong, here in the great Midland metropolis.’

The group Stahl assembled that fall included writers from both sides of this apparent divide. Garland (1860-1940) was one of the biggest stars he invited. This Wisconsin native was celebrated for Main-Travelled Roads, his 1891 set of stories describing the hardships of a boy’s life on the prairie.

Garland had moved to Chicago in 1893, announcing soon afterward: “The rise of Chicago as a literary and art centre is a question only of time, and of a very short time.” And he was determined to help make that happen. “This is where I belong, here in the great Midland metropolis,” he wrote.

Garland had moved to Chicago in 1893, announcing soon afterward: “The rise of Chicago as a literary and art centre is a question only of time, and of a very short time.” And he was determined to help make that happen. “This is where I belong, here in the great Midland metropolis,” he wrote.

Historian Donald L. Miller describes Garland as “brawny, explosive, and willfully ill mannered,” and fervent about the need for political reform. “When he preached his rural radicalism in crowded Chicago halls, his eyes would glow like hot cinders and his voice would tremble with rage,” Miller wrote in his 1996 book City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America. [24]

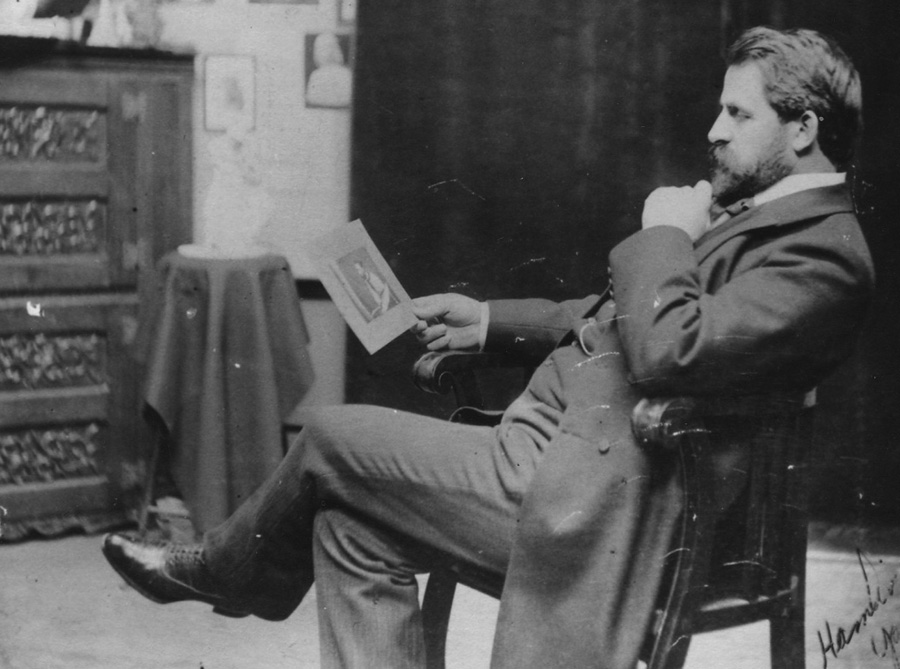

Another literary heavyweight in Stahl’s group was Hobart Chatfield Chatfield-Taylor (1865-1945). “He was a cosmopolite, but strangely, a somewhat shy and diffident gentleman with whom conservation seemed a trifle remote,” Gerstenberg observed. [25]Born into a wealthy family in Chicago, he’d added the second Chatfield to his name so he could inherit money from that side of his family. [26] He’d written novels, memoirs and a biography of Molière, and he’d also edited a literary journal called America in 1880s and 1890s. Stahl scoffed that this publication was “conducted on a plane entirely too high for the Chicago of the period of its existence.” [27]

Collections, University of Illinois at Chicago Library. Folder 52.

In the early 1890s, Chatfield-Taylor was the consul of Spain in Chicago [28] and a member of the Whitechapel Club, a group of journalists and other noteworthy Chicago citizens who took their organization’s macabre name from the London neighborhood where Jack the Ripper went on his killing spree. Their meeting room was supposedly decorated with a used hangman’s rope and the skulls of actual murderers. “The members of the Whitechapel Club were the most original, bizarre, harmlessly insane and interesting lot of men that, in the history of the Midland, shocked some and amused all, including themselves,” recalled Stahl, who met Chatfield-Taylor for the first time at a Whitechapel Club gathering. [29]

In November 1913, Chatfield-Taylor chaired a National Institute of Arts and Letterssymposium at the Art Institute, welcoming the nation’s leading painters, composers, sculptors, and writers. [30] That event may have helped inspired Stahl to bring together a group of Illinois authors.

Chatfield-Taylor and his wife—the beautiful Rose Farwell, daughter of former United States Senator Charles Benjamin Farwell [31]—were regulars at the Little Room, a gathering of influential artists and writers after Chicago Symphony Orchestra concerts on Friday afternoons. [32] The group, which usually gathered in the Fine Arts Building on Michigan Avenue, was named after an 1895 short story by Madeline Yale Wynne in Harper’s Magazine about a room that mysteriously appeared and disappeared. [33] Many early members of the Society of Midland Authors were also part of the Little Room’s “polite circle of bohemians,” [34] including Chatfield-Taylor, Monroe, Garland, sculptor Lorado Taft and authors George Ade and Edith Wyatt. According to The Encyclopedia of Chicago, the group fostered “an atmosphere of aesthetic playfulness and serious intellectual engagement that lasted until the club’s demise in 1931.” [35]

‘There were friendly groups of artists in Chicago at this time’

“There were friendly groups of artists in Chicago at this time, and they were less divided by cliques and professional barriers and jealousies than in certain other cities,” Monroe wrote. “We used to meet on Friday afternoons … to talk and drink tea around the samovar, sometimes with a dash of rum to strengthen it, and every visitor who was anybody in any of the arts would be brought to the Little Room by some local confrère,” she wrote, recalling that the group often staged “a hilarious play or costume party.” [36]

In 1907, Garland had started a more formal arts group, the Attic Club, which was all-male at first, including the men who hung out at the Little Room. “There are in Chicago many clubs, each with a special function, civil or political, but there is no association which unites all the literary and artistic forces as this club would do,” he wrote in a letter, explaining his idea for a private club including “men concerned with some form of creative art; that is to say, painters, sculptors, novelists, poets, musicians, architects, historians, illustrators and those who make handicraft and art” as well as “distinguished men in other professions who are patrons of art or sympathetic with the fundamental purposes of the club.” [37]

In 1909, the club changed its name to the Cliff Dwellers, which was the title of a Henry Blake Fuller novel about Chicago. Garland said he’d told Fuller: “It isn’t a matter of ten years or your lifetime, Fuller. We are building something in this Club which will be alive and jocund when you and I are gone, and I want its name to be characteristic of Chicago and a reminder of you and your first fictional study of Chicago life.”

Fuller replied, “Nobody will want to be reminded of me,” and refused to join the club. [38] (He would not join the Society of Midland Authors, either.)

Stahl’s idea of creating another group—one dedicated to the region’s authors—began to take shape in the fall of 1914. The authors he’d invited gathered for dinner on November 28, 1914, at the Auditorium Hotel in Chicago.

Continued in Part 2: Getting Organized.

Sources

1 — John M. Stahl, Growing With the West: The Story of a Busy, Quiet Life (London, New York, Toronto: Longmans, Green and Co., 1930), 421.

2 — Alice Gerstenberg, “Come Back With Me,” unpublished memoir, Chicago History Museum manuscripts collection, 265.

3 — Fanny Butcher, “The Society of Midland Authors,” from a talk at the dedication of the Society of Midland Authors’ club rooms on September 27, 1962, at the Sheraton-Chicago Hotel, printed in the SMA Yearbook 1963-65, 1; Society of Midland Authors Collection, Special Collections, University of Illinois at Chicago Library Supplement I, Folder 5.

4 — Stahl, Growing With the West, 422.

5 — Stahl, Growing With the West, 414.

6 — Christian Science Monitor, January 19, 1915, quoted in Stahl, Growing With the West, 427.

7 — Hobart C. Chatfield-Taylor, “Historical Sketch,” from SMA Yearbook for 1930 and other early years.

8 — Gerstenberg, “Come Back With Me,” 265-266.

9 — Stahl, Growing With the West, 370.

10 — “Dedicated to Music and the People,” Chicago Daily Tribune, December 10, 1889.

11 — Erik Larson, The Devil in the White City (New York: Crown Publishers, 2003), 181-182; William E. Cameron, The World’s Fair, Being a Pictorial History of the Columbian Exposition (E. C. Morse & Co., 1893), 211, quoted at http://www.carleton.edu/webarchive/timecapsule_1893/burnham2.html.

12 — Claire Badaracco, “Writers and Their Public Appeal: Harriet Monroe’s Publicity Techniques,” American Literary Realism, 1870-1910 23, no. 2 (Winter 1991), 35. http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/27746442?sid=21106086270093&uid=2&uid=70&uid=2129&uid=4

13 — Quoted at http://www.carleton.edu/webarchive/timecapsule_1893/burnham2.html

14 — Timothy B. Spears, “Literary Cultures,” The Encyclopedia of Chicago (James R. Grossman, Ann Durking Keating, and Janice L. Reiff, eds.; Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 483-486. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/755.html

15 — Badaracco, “Writers and Their Public Appeal,” 35.

16 — Judith Paterson, Dictionary of Literary Biography entry, quoted on Poetry Foundation website: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/harriet-monroe

17 — Harriet Monroe, “How Will 21st Century Critics Rank Artists of the Present Day?” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 12, 1912, quoted in Badaracco, “Writers and Their Public Appeal,” 37.

18 — Harriet Monroe, A Poet’s Life: Seventy Years in a Changing World (New York: Macmillan, 1938), 243-244.

19 — Badaracco, “Writers and Their Public Appeal,” 39.

20 — Judith Paterson, Dictionary of Literary Biography entry, quoted on Poetry Foundation website: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/harriet-monroe

21 — John Blades, “Writers Captured the City’s Lusty Voice,” Chicago Tribune, January 30, 1983.

22 — Harriet Monroe, A Poet’s Life, 332-339.

23 — John Blades, “Writers Captured the City’s Lusty Voice,” Chicago Tribune, January 30, 1983.

24 — Donald L. Miller, City of the Century: The Epic of Chicago and the Making of America (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 410-411.

25 — Gerstenberg, “Come Back With Me,” 266.

26 — “Alphabet Stories: C — Hobart Chatfield-Taylor,” Lake Forest-Lake Bluff Historical Society Newsletter. http://www.lflbhistory.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/alpha-c.pdf

27 — Stahl, Growing With the West, 390.

28 — “Alphabet Stories: C — Hobart Chatfield-Taylor,” Lake Forest-Lake Bluff Historical Society Newsletter. http://www.lflbhistory.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/alpha-c.pdf

29 — Stahl, Growing With the West, 388-389.

30 — “Chicagoans Hosts to National Fine Arts Bodies,” Chicago Daily Tribune, November 13, 1913.

31 — “Alphabet Stories: C — Hobart Chatfield-Taylor,” Lake Forest-Lake Bluff Historical Society Newsletter.

32 — Arthur Miller, “Lake Forest Country Places: Fairlawn, Part 2,” Donnelley and Lee Library Archives and Special Collections at Lake Forest website, May 6, 1995. http://www.lakeforest.edu/library/archives/lf-country-places/fair2.php

33 — Michelle E. Moore, “Chicago’s Cliff Dwellers and The Song of the Lark,” from Cather Studies Vol. 9: http://cather.unl.edu/cs009_moore.html; Madeline Yale Wynne, “The Little Room,” Harper’s, April 1895: http://www.loa.org/images/pdf/Wynne_Little_Room.pdf

34 — Donald L. Miller, City of the Century, 410.

35 — Timothy B. Spears, “Literary Cultures,” The Encyclopedia of Chicago.

36 — Harriet Monroe, A Poet’s Life, 197.

37 — The Cliff-Dwellers: An Account of Their Organization, the Dedication and Opening of Their Quarters, Constitution and By-Laws, Officers, Committees, and List of Members (Chicago: 1910), 6.

38 — William Getzoff, “A Literary Puzzle,” remarks to a joint meeting of The Cliff Dwellers and the Chicago Literary Club on April 14, 2003, quoted by Gary T. Johnson in “What a Global City Can Learn from The Cliff Dwellers – Past, Present and Future,” an address to The Cliff Dwellers on November 27, 2007. http://www.chicagohistory.org/documents/home/aboutus/from-the-president/speeches-and-articles/CHM-CliffDwellersCentenaryAddress.pdf